How To Talk Like Bush

What you say: Oh Ginger, that was a bad thing. You’re a bad, bad dog, Ginger.

What a dog hears: Blah Ginger, blah blah blah. Blah blah blah blah, Ginger. — "Far Side" Cartoon

What Bush says: And when you engage the terrorists abroad, it causes activity and action.

What sticks in people’s minds: …engage the terrorists…activity…action.

What we do with words, wild chimpanzees do with lice. Instead of nitpicking, we humans use "demonstrative" rhetoric (epideictic in Aristotle’s book), the kind of persuasion that brings us together and distinguishes us from other groups. Demonstrative rhetoric exploits our instinct for forming tribes and rivalries, and our fear of being an outsider. “If men were not apart from one another,” said the twentieth-century rhetorician Kenneth Burke, “there would be no need for the rhetorician to proclaim their unity.”

What we do with words, wild chimpanzees do with lice. Instead of nitpicking, we humans use "demonstrative" rhetoric (epideictic in Aristotle’s book), the kind of persuasion that brings us together and distinguishes us from other groups. Demonstrative rhetoric exploits our instinct for forming tribes and rivalries, and our fear of being an outsider. “If men were not apart from one another,” said the twentieth-century rhetorician Kenneth Burke, “there would be no need for the rhetorician to proclaim their unity.”

The more people find themselves divided, the more they engage in demonstrative gestures — a great speech like the Gettysburg address, or a heartfelt apology by a lover who nonetheless thinks he did nothing wrong. It can be a song, like the chants soldiers use when they march, or the tunes kids swap on the Web. Even a common dialect — slang, jargon, or political code words — lets people demonstrate how they belong together.

The Responsibility to Hug

Pundits love to talk about George W. Bush’s Christian code, but that’s only part of his grooming shtick. He also has his male code, his female code, and his military code. Bush speaks a pure language of identity, favoring the present tense and using terms that resonate among various constituencies. When he speaks the faithful, for example, he prefers “I believe” to “I think.” In the summer of 2001 he used “believe” as a kind of fugue:

“I know what I believe. I will continue to articulate what I believe and what I believe—I believe what I believe is right.”

Believe it.

Before his re-election, Bush appealed to women with sentences that began “I understand,” and he repeated words such as “peace” and “security” and “protecting.” For the military, he used “never relent” and “whatever it takes” and “we must not waver” and “not on my watch.” For Christians, he began sentences with “And,” just like the Bible:

“And in all that is to come, we can know that His purposes are just and true.”

For men, he used swaggering humor that implied he personally pulls the military trigger:

“When I take action, I’m not going to fire a two million dollar missile at a ten dollar empty tent and hit a camel in the butt. It’s going to be decisive.”

So what? Every politician uses code words. What makes Bush different is his masterful way of using code words without the distraction of logic. He speaks in short sentences, repeating code phrases in effective, if irrational, order. “See, in my line of work you got to keep repeating things over and over and over again for the truth to sink in,” he once said, “to kind of catapult the propaganda.”

But he does more than just repeat things over and over and over. He catapults his messages by leaving logic out of them. The result is what the poet Robert Frost called the “sound of sense” — the meaning you intuit from hearing people speak in the next room. You pick up the sense from the speakers’ rhythms and tone, and from an occasional emphasized word. If you ever played Sims on your computer, you know what I mean. The game’s simulated characters speak Simlish, a babble language invented by a pair of improv comedians. (An angry character will exclaim something like, “Frabbida!”) You suss out much of what they say by their tone of voice. Bush’s strange statement, “Families is where our nation finds hope, where wings take dream,” makes an almost poetic sense. It has the sound of sense. He has a masterful way of combining repetition, tone and code words unfettered by context.

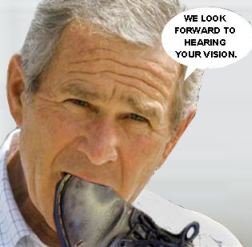

“We look forward to hearing your vision, so we can more better do our job.”

This is a classic Bushism, fractured syntax that seems to come out of a short circuit in the language center of his brain. You know what he means, though, don’t you? If you heard it instead of read it, you would probably miss the “hearing your vision” part and come away with “look forward” and “hearing” and “vision” and “do our job.” The resulting message conveys optimism, listening, and duty. Bushisms treat audiences like the dog in the Far Side cartoon.

The Italic Slant

Clearly, Bush didn’t practice speaking Bushimistically. But he has done nothing to fix his syntax, probably because he benefits from it. Logic-free speech italicizes the words he wants to stick in our heads. When he says,

“We’ll be a great country where the fabrics are made up of groups and loving centers,”

he isn’t painting any sort of realistic picture of America. You couldn’t even call his technique “impressionism.” It’s more like pointillism, dotting the rhetorical canvas with values to create a group identity. As he himself succinctly put it, “sometimes pure politics enters into the rhetoric.” It’s his job as a politician to keep everything else out, leaving only politically useful values. “I’m a proud man to be the nation based upon such wonderful values,” he says.

What Bush says: Part of the facts is understanding we have a problem, and part of the facts is what you’re going to do about it.

What sticks in people’s minds: … facts … understanding … problem … facts.

The distracted listener gets the impression of an engaged, knowledgeable leader.

Skeptical? That’s probably because you’re receiving this in print, a logical medium. A good reader absorbs whole paragraphs, not words or phrases. Imagine hearing a Bushism on television while you’re making dinner and the dog is barking and the kids are arguing over who got to use the Play Station last and you’re wondering whether it’s time to get an oil change. A great Bushism is a work of art—neither an accurate representation of reality nor an appeal to logic, but a series of impressions that bring Bush closer to the group he wants to appeal to.

What Bush says: I believe we are called to do the hard work to make our communities and quality of life a better place.

What sticks in people’s minds: … believe … called … hard work … communities … quality of life … better place.

Bush attracts red state voters by emphasizing the values of hard work, quality of life, and making our community a better place. He also injects the Christian code words “believe” and “called” (a Christian is called by God to fulfill his mission in life). He uses these code words efficiently, with a brevity impossible in a logical sentence.

What Bush says: And so during these holiday seasons, we thank our blessings.

What sticks in people’s minds: … holiday season … thank … blessings.

Try using each code phrase with proper grammar and syntax. “And so, during this holiday season, we thank the Maker for all our blessings.” That takes four more words than Bush’s more efficient usage, and requires the politically tricky mention of a higher deity. Bushisms carry the risk of being unintentionally hilarious.

What Bush says: Too many good docs are getting out of the business. Too many OB/GYN’s aren’t able to practice their love with women all across the country.

What sticks in people’s minds: … good docs … love … women.

But despite his gaffes, he stays on message with an unshakeable determination. In a speech to Native American tribes, he delivers a single message — tribes are sovereign entities — by repeating it. No other concept muddies these sovereign waters.

What Bush says: Tribal sovereignty means that, it’s sovereign. You’re a — you’ve been given sovereignty, and you’re viewed as a sovereign entity. And, therefore, the relationship between the federal government and tribes is one between sovereign entities.

What sticks in people’s minds: Tribal sovereignty … sovereign … sovereignty… sovereign entity… sovereign entities.

The fact that his statement didn’t actually state anything is nothing new. Politicians rarely say anything that could get them in trouble. Bush does this tradition one better by repeating a commonplace or value and using code words like “sovereignty” that appeal to the particular audience.

What Bush says: The goals for this country are peace in the world. And the goals for this country are a compassionate American for every single citizen. That compassion is found in the hearts and souls of the American citizens.What sticks in people’s minds: … goals … peace … goals … compassionate … compassion … hearts and souls.

What Bush says: It’s a time of sorrow and sadness when we lose a loss of life.

What sticks in people’s minds: …sorrow…sadness…loss…life.

Now You Try It

Experiment on your own. Take rational, fully articulated thoughts and reduce them to logic-free collections of values.

Rational thought: Boys, we can win this one. We’re bigger in size, we’ve practiced harder, and we have the better game plan.

Logic-free values: Men, get out there. Be big. Be hard. Work the plan. Win the game.

Rational thought: Don’t be scared. There aren’t any monsters under the bed.

Logic-free values: You’re safe. I’ll be safe here, protecting you, in your own warm bed.

To speak in Bushisms or other effective code language, choose the words that work, and avoid denying words that trigger a bad response. If you say “Don’t be scared,” a kid may hear, “Scared.” If you say, “There aren’t any monsters under the bed,” the kid hears, “…monsters under the bed.” On the other hand, you can use denial to mean the exact opposite of what you’re literally saying, as Bush did when he described how Iraqis received our troops.

What Bush says: I think we are welcomed. But it was not a peaceful welcome.

What sticks in people’s minds: … welcomed. … peaceful welcome.

The technique is harder than it looks. It takes a great deal of practice to be able to paint a value-packed, logic-free picture like this one that Bush created early in the Iraq War.

“There’s only one person who hugs the mothers and the widows, the wives and the kids upon the death of their loved one. Others hug but having committed the troops, I’ve got an additional responsibility to hug and that’s me and I know what it’s like.”

How many code words can you find hidden in that pointillist picture?

Blue staters have a hard time with this kind of fractured code language. They prefer a Bill Clinton or John Kerry who can speak whole, logical, publishable thoughts. But John Kerry lost the election in part because he tried to win his arguments while Bush focused on identity. In a formal debate, as the ancients said, rhetoric is verbal jousting. But in human society, as the modern rhetoricians say, rhetoric is social glue. — Jay Heinrichs